If you missed Part One click here

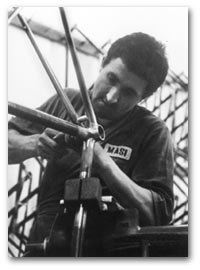

At the US Masi factory in Carlsbad, Mario oversaw

production of some 2,200 bicycles over the course of three years. To reach

that level of production, Mario was required to train a number of Mexican

workers. They were hired to do the majority of the preparation work that

goes into building a frame.

Mario's widowed wife, then girlfriend, Lisa recalls, "Mario respected

the Mexican guys who helped him. They would often have lunch together,

Mario enjoyed the tortillas. These men would come up from Mexico and make

a sacrifice to take care of their families, send home every penny. These

were the people that Mario admired, people who worked hard and took care

of their families. He was so Old World."

However, when it came to building and marketing bicycles Mario anything

but "Old World". In an effort to conquer the US bicycle market, Faliero

Masi and Mario went to the Encino velodrome one evening. The reigning

sprinter of the 70's, Jerry Ash was at the track working out. He was

offered a Masi track frame.

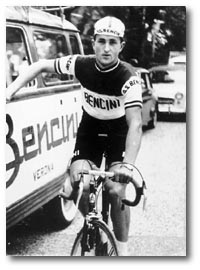

Ash recounts, "Before I received the Masi, I was riding a Rickerts and

before that, a Paramount. I went to the Masi factory at Carlsbad and I was

measured for the frame which Mario then built. I wanted an all-around

track frame that would be good for sprinting. The ride of the bike was

tremendous."

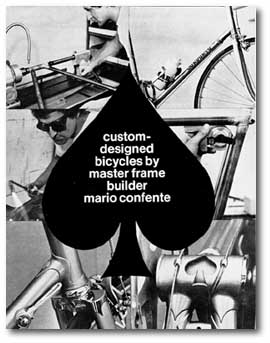

Custom Bicycles by Confente was located in Los Angeles. One of the

first things Mario did was contact Jerry Ash and offer to build him a road

and track bike. Ash went on to ride the Confente track frame in the World

Championships in 1976, 77, and 78. In 1977, he finished seventh in the

match sprints, the highest finish for an American in over a decade. Before

long, other top riders, including Jonathan Boyer, were traveling to Los

Angeles for a Confente frame.

Lisa recalls that Mario poured his heart and soul into this new

venture. "He worked like a fiend. I would have to tear him out of the

place in LA. He would not leave until it was spotless clean. I would help

him sweep the floor - anything to get him out of there!"

Confente frames were the rage at the New York bicycle show the first

year that they were unveiled. Tom Kellogg, of Spectrum Cycles, recalls,

"Mario made beautiful stuff and he pushed the American builders beyond a

look that we all had, which was kind of simple, plain lines. He forced us

to class up our act. Mario's frames were the first to combine American

quality and the Italian look. That had never been done before. Fairly

rapidly after that the Americans made their frames look slicker."

Ben Serotta adds, "After seeing Confente's bikes at the New York show,

it was clear that he raised the standard." Richard Sachs recalls looking

at the Confente brochure and shaking his head in disbelief that someone

could charge $400 for a custom frame. At the time, Sachs was charging $180

for a custom frame. Sachs notes, "I remember asking myself, what could a

builder possible do to a frame to make it cost so much more?"

As beautiful and skillfully made as the Confente frames were, they were

also expensive. Recht decided to capitalize on Mario's name and

innovations. Unbeknownst to Mario, Recht was preparing to launch another,

less expensive bicycle frame. When Mario ordered 100 dropouts for the

Confente bicycles, Recht ordered 200. The Medici frame was to be unveiled

at the next New York bicycle show. Prior to the show, Confente learned

that his name was going to be used to launch this new frame. He perceived

the Medici frame to be an inferior product. He promptly handed in a letter

of resignation and was immediately locked out of the factory. Unable to

retrieve his tools, Confente headed north to the one place where he knew

he could continue to build frames, Monterey.

Mario had traveled to Monterey previously to meet with Boyer and a

sponsor of Boyer's, George Farrier. Farrier had a machine shop in his

garage and Confente was impressed by the size of the shop. In the year

that followed, he worked without distraction. Farrier recalls the day

Mario showed up at his property, "Mario pulled into the driveway in his

car. I was surprised to see him. I asked him what he was doing here and in

his thick Italian accent he said that he was here to build bicycles."

While Farrier's accommodations were first class, Mario still longed for

his own shop. He and Jim Cunningham put together a business plan. In

addition to developments in his career, Mario's personal life was taking a

new step forward. Mario proposed to his longtime girlfriend and the two

were married shortly thereafter.

Lisa remembers, "I left Mario. I went to Houston for a while. I wanted

to get married and I knew that he would never marry me. He sent a lot of

money home to Italy. Yet, Mario thought you had to have a lot of money to

be married. I had a little house in Encinitas and I believed that we would

be all right. When I realized it wasn't going to work out, I said that I'm

out of here, we've been together for five years and there is no future.

Mario was bummed out and very lonely after I left California. Six months

later, when I returned from Texas, he asked me to marry him."

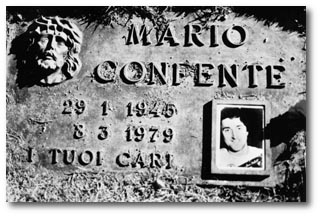

The newlyweds settled into Encinitas and Mario renovated the garage

into his new shop. Sadly, as Mario was on the verge of achieving his

dream, he abruptly passed away. Mario and Lisa were married less than two

weeks. An autopsy later revealed that he had an enlarged heart and

suffered from heart disease. Lisa remembers Mario on his last morning, "He

was going to go back to Masi to work for a short time, just to make some

cash. He was supposed to meet with the Masi foreman that morning. He was

really upset and stressed about going back there. I felt like it was

something he didn't want to do, yet he felt he had to."

If you have questions or comments, please contact

Russ Howe

|

Faliero Masi sold the rights of the Masi name to San Diego

businessman Roland Sahm. Under their agreement, Masi bicycles would be

built in the United States. Failero came to supervise the start of the new

venture. He brought Mario with him to initiate production.

Faliero Masi sold the rights of the Masi name to San Diego

businessman Roland Sahm. Under their agreement, Masi bicycles would be

built in the United States. Failero came to supervise the start of the new

venture. He brought Mario with him to initiate production.

She

also recalls meeting Eddy Merckx when they traveled to Italy together. "We

went in when Eddy was getting a massage. He was getting ready to ride the

Milan-San Remo race. Eddy said, "hey Mario, I love your bikes and I want

another bicycle." Mario said that he made many bikes for him but he would

always put his own decals on the frame. One thing that was sad about Mario

being in the U.S., is that he did not have a strong command of the

language. In Italy, he was like another person, he was so strong over

there. We went to see Signor Campagnolo, Eddy Merckx, Signor Cinelli and

all of these people. They way he spoke to them was so different then how

he was over here."

She

also recalls meeting Eddy Merckx when they traveled to Italy together. "We

went in when Eddy was getting a massage. He was getting ready to ride the

Milan-San Remo race. Eddy said, "hey Mario, I love your bikes and I want

another bicycle." Mario said that he made many bikes for him but he would

always put his own decals on the frame. One thing that was sad about Mario

being in the U.S., is that he did not have a strong command of the

language. In Italy, he was like another person, he was so strong over

there. We went to see Signor Campagnolo, Eddy Merckx, Signor Cinelli and

all of these people. They way he spoke to them was so different then how

he was over here."

While it was encouraging that top riders were bringing

recognition to the new Masi venture, Mario was not content. The one thing

that eluded him up to this time was the chance to build frames bearing his

name. As the Masi California operation struggled, a New Jersey

businessman, Bill Recht, attempted to buy the business from Roland Sahm.

Unable to reach an agreement, Recht did succeed in hiring Mario away from

Masi. Mario would finally build a bike with his name on the downtube. It

was a dream come true, or so he thought.

While it was encouraging that top riders were bringing

recognition to the new Masi venture, Mario was not content. The one thing

that eluded him up to this time was the chance to build frames bearing his

name. As the Masi California operation struggled, a New Jersey

businessman, Bill Recht, attempted to buy the business from Roland Sahm.

Unable to reach an agreement, Recht did succeed in hiring Mario away from

Masi. Mario would finally build a bike with his name on the downtube. It

was a dream come true, or so he thought.

The next thing she remembers, "This biker guy found him... a

Hell's Angel kind of guy. He banged on the door, it was 5:30 or 6:00am. ,

he says, "Lady, lady there is a man out here and I think he is dead." I

went out there and saw him lying in the road. I just lost it. All I said

was, "are his hands okay? He works with his hands." He wasn't breathing or

anything. For some reason my car was in the middle of the road. He may

have been trying to move my car. He was found beside the car, sort of out

in the road."

The next thing she remembers, "This biker guy found him... a

Hell's Angel kind of guy. He banged on the door, it was 5:30 or 6:00am. ,

he says, "Lady, lady there is a man out here and I think he is dead." I

went out there and saw him lying in the road. I just lost it. All I said

was, "are his hands okay? He works with his hands." He wasn't breathing or

anything. For some reason my car was in the middle of the road. He may

have been trying to move my car. He was found beside the car, sort of out

in the road."

The cycling community was stunned by the death of Mario

Confente. In his all to brief career, he was transforming the cycling

industry. With the talent and passion that he possessed, one can only

wonder about the frames he would be building today. One can only wonder

about the man he would be today.

The cycling community was stunned by the death of Mario

Confente. In his all to brief career, he was transforming the cycling

industry. With the talent and passion that he possessed, one can only

wonder about the frames he would be building today. One can only wonder

about the man he would be today.